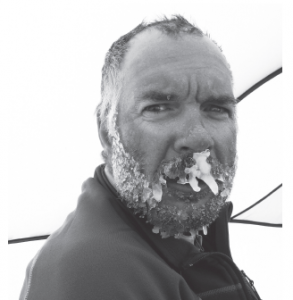

After saving a few lives on Everest's North Ridge, Warner was struck by an errant oxygen canister—and had to save himself.

The post A Head Injury in the Death Zone: Chris Warner’s Close Call on Everest appeared first on Climbing.

While today reality TV feeds us a steady diet of packaged petty dramas, in 2003 the concept was radical. Our team of six contestants and a dozen Sherpas and cameramen was to be the first to try to bring it to the summit of Everest. Three dozen of us headed to Tibet in early April, set up an elaborate base camp, and filmed just about every silly thing. My favorite emotional breakdown came after a failed plan to climb to Camp 3, when one of the contestants whined, “We are elite endurance athletes. Stop yelling at us!”

Having guided the North Ridge of Everest twice before, I was cast in the role of senior guide. The North Ridge is an amazing route, with a difficult summit day. Above Camp 3, the ridge is too steep to attack head on, so the route heads out onto the face, weaving in and out of layers of sedimentary rock and up steep snow slopes and short rock steps. Finally, the slope eases to 10 or 15 degrees, and here, dug into the snow, are the terraced tent sites of high camp.

From high camp, summit day involves climbing technical cliff bands (three steps) and, I regret to say, stepping over eight frozen bodies. When we studied how these climbers died, all descending from the summit, the common theme is that they sat down. At these extreme temps, death can come fast—the waving man froze to death sitting on a rock, his hand still in the air—or slowly: Fran Arsentiev, who lies on the tilted slope at the base of the fixed lines, died two days after summiting. You won’t see her husband, Sergei Arsentiev, because he fell from the North Face while trying to organize her rescue.

Your chances of dying on Everest increase over time: the time spent climbing to and from the summit. When, on the early afternoon of May 22, our TV show reached high camp, the teams that had left the night before were still trying to reach the summit. It was long past the standard turn-around time of 11:00 a.m.

The year 2003 was the 50th anniversary of the first summit of Everest, and the whole mountain was crowded. Compounding the overcrowding, the 22nd was a marginal weather day with gusting winds and at times blowing snow. As a Kuwaiti climber later wrote, it was “a long hard day, especially for non-pure mountaineers and non-athletes.” Among the 50 climbers strung along the North Ridge, the inexperienced struggled with the technical challenges and created chaos at the Second Step when they fell and swung out on their jumars.

High up, in a mixture of ambition and incompetence, climbers kept stumbling toward the summit. Darkness caught them. Our radios crackled with slurred conversations as guides, Sherpas and clients steadily tired. Oxygen bottles dried up. Weakened climbers stumbled. Teams split. People were suffering from hypothermia, snow blindness, cerebral edema and frostbite.

Jake Norton, our show’s photographer, and I left the tents and spent the night searching the slopes for survivors. We guided more than two dozen climbers back to the tents. The bottles of oxygen we had hoped to summit with were consumed by victims. Our cameramen cuddled hypothermic climbers, trying to warm them. The reality-show contestants melted water for the dehydrated. Sherpas injected Dexamethasone, a corticosteroid, into the quads of those with swelling brains.

Our summit bid became a trauma scene. Triage trumped TV. By a miracle everyone survived the night.

Once the sun hit camp, the rescue continued. We tied the worst-off folks to short ropes and guided and lowered them down slopes and over rock steps. I found myself running a rescue operation at 27,500 feet with over 45 climbers somehow involved. In my hands was a rope tethered to a snowblind climber. Exhausted and unable to see the next foothold, he had to be convinced to take each step. It took nearly an hour to lower him 300 feet.

Below the tents the slope stretched for 250 feet, gently tilted but covered with a layer of windblown ice slabs. Crampons were crucial. A slip here would send you tumbling 7,000 feet down Everest’s North Face. A few years before I had watched a Russian climber cartwheel down this same face. His arms and legs flapped as he flew past, slamming with a bone-crushing thud onto a rock slab, and then bouncing into the shadowed Great Couloir. He ricocheted from side to side, and finally was swallowed by the bergschrund.

My snow-blind climber needed to rest, and we stopped for a breather. A few feet above me stood a cameraman, Michael Brown. The slopes around us were filled with small groups struggling to descend. Each team of two or three was working through its own epic: trying to help a climber with frostbitten hands grip a rope, caring for a cerebral-edema victim fighting anxiety, pleading with an exhausted climber to keep moving.

Back at the tents, 335 feet above us, a Sherpa was gathering his team’s gear. He emptied sleeping pads, stoves and pots from the tent, and tossed out an oxygen bottle.

An oxygen bottle weighs 6.6 pounds. It is constructed of Kevlar or fiberglass and “spun” to create a cylinder. Coming out of the top end is a two-inch threaded pipe that screws into the climber’s regulator, where a hose leads to the oxygen mask. The oxygen cylinder is incredibly strong so it won’t explode. The bottles are painted bright orange to make them easy to find in the dark. That paint makes them extra slippery.

The cylinder landed on the windblown ice slope, rocketed down it, and launched off the cliff band, an airborne 6.6-pound missile. The point of impact was the back of my skull.

Imagine the crack of an aluminum bat hitting a fastball, but with a layer of flesh and hair dulling the high pitch and amplifying the bass. It is a sound you feel in your soul. The bottom of the tank (luckily, not the threaded pipe) slammed my head forward, twisting every resistant muscle, vertebrae and ligament in my neck, popping the brain from its soft stem, flinging it into the frontal bones of the skull, and shocking the occipital nerve, which originates in the part of the brain that was directly impacted, into a high-pitched vibration. I was blinded both by the pain and the pulsing electric shocks of the malfunctioning nerve.

Michael grabbed the radio clipped to the shoulder strap of my pack. “Chris is dead!” he said, and I would have looked like it. Radios up and down the mountain sang with the words of people sickened by the sound of the impact and gripped by fear of more flying bottles.

Over a 30-plus-year career as a guide, I’ve been certified and re-certified in wilderness medicine a dozen times. The concept of Increasing Cranial Pressure always comes up. It means swelling of the brain and can be fatal. I was blind and at the edge of consciousness. The instantaneous migraine and nausea were terrible, but it was the risk of seizures and coma that worried me. I was at 27,000 feet and didn’t want to die up there. I thought of the sorrow on the faces of those bodies I had walked around on so many 8,000-meter peaks. We might comfort ourselves by saying they died doing what they loved, but I can tell you they died cold, hungry and lonely. No one wants to spend eternity like that.

My only hope was to descend as fast and far as possible, while I could. Relying on instinct and training, I wrapped my arms around the ropes and stumbled and slid down the slopes. I fought to Camp 3, where I grabbed the pack straps of Kari Kobler, an old friend and leader of a Swiss expedition, and he led me through the loose rocks and drifting snows along the crest of the ridge toward the North Col. As the hours passed, my vision went from black to Jell-O. I was now looking through a foot-thick block of clear Jell-O, but with the vibrating nerve, every blurry thing jumped up and down. As we descended, the Jell-O thinned, though the objects kept jumping. I reached the North Col by early afternoon and was guided by a Sherpa into ABC as the sun set.

It took me five days, by foot, jeep and jet, to make it from high camp on the Tibetan side of Mount Everest to the offices of the neurosurgeons at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. They pumped me full of dyes and examined my brain.

Dr. David Newman-Toker told me: “It looks like you were in a motorcycle accident without a helmet, and your head bounced and bounced on the pavement.”

Showing me the computerized images, he pointed out the damage. “These are all scabs. And these are shear planes, caused where layers of your brain moved at different but incredibly fast speeds. It will take at least a year for this to heal.” One of his partners told me that I was an idiot (for climbing Everest), but a lucky one (for not being permanently brain damaged).

The vibrating vision lasted for weeks. It was almost six months before I could exercise again: a simple push-up would trigger exercised-induced migraines confining me to bed, where I had to lie in complete silence and darkness for hours.

I was extremely lucky, both to be alive and to recover quickly and completely. Eight months after the accident I was guiding in Ecuador. Twelve months later I summited Lhotse without oxygen.

A lot of us were lucky that season on Everest. Thankfully, no one died during the epic descent from the mountain. Two of the TV contestants and a bunch of the crew summited Everest a week after the rescue. And I am still climbing.

Chris Warner has summited five 8,000-meter peaks, soloed the South Face of Shishapangma, and pioneered routes on Ama Dablam and Shivling. He founded Earth Treks climbing gyms and is the author of High Altitude Leadership.

The post A Head Injury in the Death Zone: Chris Warner’s Close Call on Everest appeared first on Climbing.